What is DNS? Link to heading

The internet is a vast interconnection of systems across the world. Each host connected to the internet is assigned an IP (Internet Protocol) address, uniquely identifying each connected host.

Imagine a world where you go to your browser and put in 207.241.224.2 to see the internet archives or 20.207.73.82 to code collaboratively. Soon everybody would require a phone book to use the internet.

Domain Name System or DNS is a lookup functionality for the internet, translating human-readable addresses like github.com to their corresponding IP addresses (e.g., 20.207.73.82).

How does DNS actually work? Link to heading

The address resolution happens through the following steps:

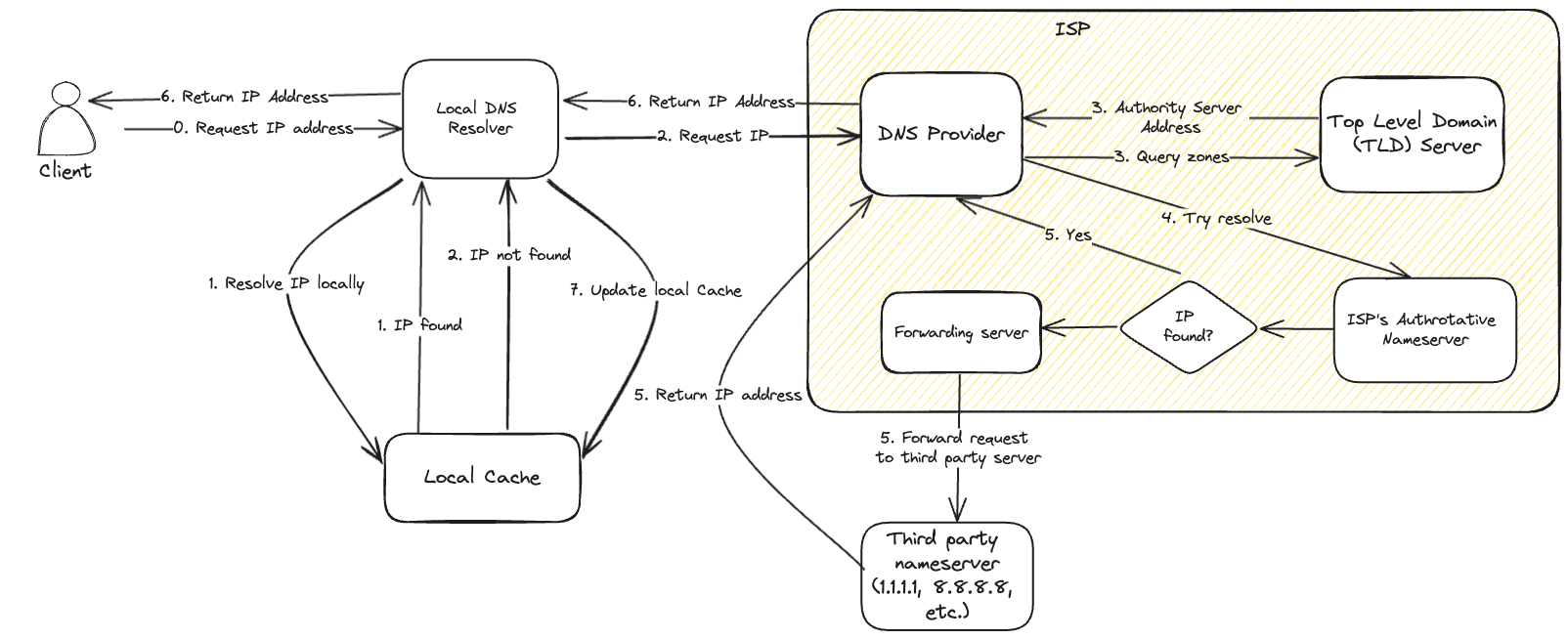

DNS IP resolution flow

- The client makes a request to resolve a domain name to an IP address to the recursive servers (DNS resolvers) in the client.

- The DNS resolver checks for the IP address in its local cache. If found, the address is returned. If not, the request is forwarded to the ISP’s DNS resolver.

- The ISP’s DNS resolver queries the Top Level Domain (TLD) nameservers to find the DNS zones. The TLD servers return the details of the authoritative nameserver where the request can be resolved.

- If the TLD servers return the information of the ISPs authoritative nameserver, then the request is forwarded to the ISPs authoritative nameserver. ISP’s nameservers are generally not very reliable.

- If the DNS record is not found in the ISPs authoritative nameserver, then the request is sent to a forwarding nameserver which send the request to third party authority nameservers such as

1.1.1.1(Cloudfare) or8.8.8.8(Google) to resolve the IP address. - The authoritative nameserver queries for the appropriate DNS records by looking up the A record or AAAA record. If there’s a CNAME record, the authoritative server also returns the canonical name. If no matching record is found, the server responds with an NXDOMAIN (non-existent domain) message. IP address is resolved from the respective record and returned to the ISP’s recursive nameserver.

- The ISP’s recursive server then returns the response to the client’s DNS resolver. The DNS resolver returns the response to the client.

- At the end, the local cache updated with the IP address with a TTL (Time-To-Live) from the DNS record returned from the authoritative server.

This process happens quickly and transparently to the end user, allowing them to access websites and services using human-readable domain names.

DNS Records: CNAME, A, AAAA, PTR Link to heading

CNAME Link to heading

CNAME or a Canonical Name is used to set an alias to a different domain while keeping the same IP address allowing multiple domains to share the same IP address and web content while still having separate domain names.

For example, if you have a website with the domain name example.com, you can create a CNAME record for blog.example.com that points to example.com, allowing users to access the same website with two different domains, example.com and blog.example.com.

When a user uses an alias domain name, DNS will use the CNAME record associated with the alias domain to look up the correct canonical domain name. For example, when a user enters blog.example.com in their browser, DNS will check the CNAME record, which would point to example.com and then use the example.com domain name to find the IP address.

A Record Link to heading

An A record or an Address record is a type of DNS record used to map a canonical domain name to an IP address. An A record maps a domain name to an IPv4 address, allowing browsers to locate the correct server for a website.

It is important to note that a domain name can have multiple A records, each with a different IP address to support highly available load-balanced systems having redundant servers to handle failovers.

AAAA Record Link to heading

The Quad A (AAAA) record is similar to an A record, but it’s used for IPv6 addresses instead of IPv4. If a domain has both A and AAAA records, then DNS will first try to resolve the domain using the AAAA record, and if that fails, it will fall back to using an A record.

PTR record Link to heading

PTR record is the inverse of A record i.e. a PTR record is used to query a domain name from an IP address. When a user attempts to reach a domain name in their browser, a DNS lookup occurs, matching the domain name to the IP address. A reverse DNS lookup is the opposite of this process: it is a query that starts with the IP address and looks up the domain name 1.

PTR records are used in reverse DNS lookups; common uses for reverse DNS include:

- Anti-spam: Some email anti-spam filters use reverse DNS to check the domain names of email addresses and see if the associated IP addresses are likely to be used by legitimate email servers.

- Troubleshooting email delivery issues: Because anti-spam filters perform these checks, email delivery problems can result from a misconfigured or missing PTR record. If a domain has no PTR record, or if the PTR record contains the wrong domain, email services may block all emails from that domain.

- Logging: System logs typically record only IP addresses; a reverse DNS lookup can convert these into domain names for logs that are more human-readable 1.

DNS Zones Link to heading

DNS zone is a part of the DNS domain name which is used by a TLD nameserver to recursively fetch the authoritative nameservers that might contain the IP address of the domain. For example, for www.example.com, mail.example.com, the zone would be example.com

DNS Zone transfer Link to heading

DNS servers in a zone are configured with a zone file. A zone file is configured with the complete description of a zone. A DNS server loads all the data of a zone through zone file.

Generally a DNS zone has a primary server, which has the zone file, resolves the DNS entries and updates the DNS records. To build redundancy, Secondary DNS servers are created which to add redundancy with the DNS servers. In this case, a zone file is loaded in the secondary server from the primary server. This process is called a zone transfer. Providers like Cloudflare provide setting up secondary DNS for improved resiliency and performance.

SOA Link to heading

SOA or Start of Authority is a record in the DNS system that specifies the authoritative information about a domain, including the domain’s primary name server, the domain administrator’s email address, and various other parameters that determine the behavior of the domain’s DNS server.

The SOA record is the first record in a DNS zone file and is used by other DNS servers to determine the authoritative source of information for a particular domain. It also defines the refresh interval, which is the time a secondary name server waits before checking for updates from the primary name server, and the retry interval, which is the time a secondary server waits before trying to contact the primary server again if it fails to respond.

The information in the SOA record is crucial for the proper functioning of the DNS system and for ensuring that the correct information is available for a given domain.

DNS Servers: Root, Authoritative, and Recursive Link to heading

DNS servers or name servers in DNS store and provide information about specific domains, responding to queries about the domain’s DNS records. They act as a central repository for information about a domain, including its IP address, mail servers, and other information required to route and deliver requests to the correct destination.

When a nameserver does not have the required record, it sends a hint also known as a referral to a different querying DNS server

There are different types of nameservers:

Root Servers Link to heading

DNS root servers are the starting point of the DNS hierarchy. They are at the top of the DNS tree structure. The root servers contain information about the TLD Servers. A root server never resolves a domain, rather it helps the DNS recursive servers reach the correct TLD server.

There are 13 root servers, which are a network of hundreds of servers running in different countries around the world.

Authoritative servers Link to heading

Authoritative name servers are responsible for storing the actual DNS records for a domain. They are the ultimate source of truth for information about the domain and respond to queries about the domain’s records.

Recursive servers Link to heading

Recursive nameservers are also called the DNS resolvers. Recursive name servers are used by client devices to resolve domain names to IP addresses. They receive a request to resolve a domain name and forward the request to the appropriate authoritative name server, returning the response to the client device.

The domain owner can configure the name servers for a domain specified in the domain’s SOA (Start of Authority) record. Other parts of the DNS system use the information provided by the name servers to route and deliver requests to the correct destination.

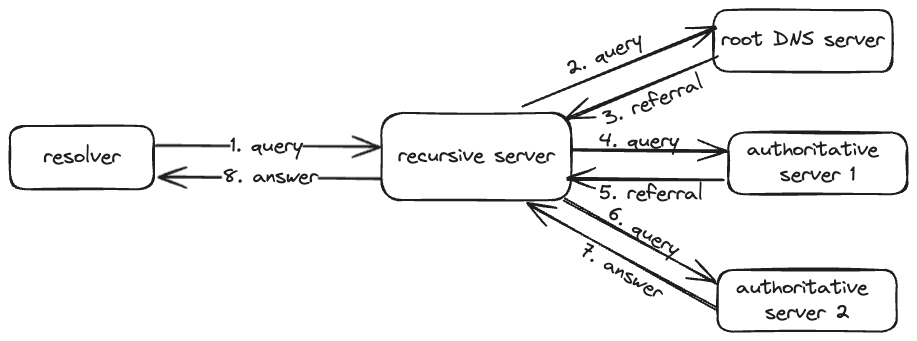

A DNS resolver generally sends a query to a recursive DNS nameserver. A recursive nameserver is responsible to follow up on every referral that the root and authoritative nameservers send. Servers that return a referral do not perform recursive lookups.

Recursive DNS resolution

TLD servers Link to heading

TLD nameservers are used to store and query the information of authoritative nameserves based on DNS zones.

For example, there would be different TLD servers for zones like .com, .net, etc.

Forwarding servers Link to heading

Forwarding nameservers forward DNS queries to different nameservers instead of resolving the addresses themselves. A DNS server sends an iterative query to a forwarding server. If the forwarding server is configured to be a forwarder, the forwarding server can send a recursive query to upstream DNS servers to get an answer.

DNSSEC Link to heading

DNSSEC is a set of security extensions to DNS that provide authentication and data integrity for DNS information. It uses public-key cryptography and digital signatures to secure DNS information and prevent tampering and malicious attacks, such as cache poisoning and DNS spoofing.

DNSSEC introduces several new types of DNS records:

- DS (Delegation Signer) record: Used to link a child domain to its parent domain and establish the chain of trust.

- DNSKEY record: Contains the public key used to verify the digital signature of the RRSIG record.

- RRSIG (DNSSEC Signature) record: Contains the digital signature for a specific DNS record.

- NSEC (Next Secure) record: Provides proof of the non-existence of a DNS record.

NSEC Link to heading

NSEC is a specific type of DNSSEC record used to prove the non-existence of a DNS record. It helps prevent cache poisoning attacks by providing cryptographic proof that a queried name or type does not exist in a zone.

When a DNS query is made for a non-existent domain or record type, instead of simply returning a “not found” message, an NSEC-enabled server will return:

- The name of the previous existing domain in canonical order.

- The name of the next existing domain in canonical order.

- A list of record types that exist for the previous domain name.

This response allows the resolver to verify that the queried name truly doesn’t exist between these two existing names, thus providing “authenticated denial of existence.”

By using DNSSEC with NSEC records, the DNS system can ensure that users receive accurate information, whether that information is positive (the record exists) or negative (the record does not exist). This comprehensive approach to security helps maintain the integrity and trustworthiness of the DNS system as a whole.

Troubleshooting DNS Link to heading

Lets take a look at how to use different tools like nslookup and dig for troubleshooting DNS.

nslookup Link to heading

nslookup’s description from its man page:

Nslookup is a program to query Internet domain name servers. Nslookup has two modes: interactive and non-interactive. Interactive mode allows the user to query name servers for information about various hosts and domains or to print a list of hosts in a domain. Non-interactive mode is used to print just the name and requested information for a host or domain.

Let’s see an example

$ nslookup github.com

Server: 8.8.8.8

Address: 8.8.8.8#53

Non-authoritative answer:

Name: github.com

Address: 20.207.73.82

nslookup also supports params to see PTR records and Mail Exchange (MX) information.

$ nslookup -type=PTR github.com

Server: 8.8.8.8

Address: 8.8.8.8#53

Non-authoritative answer:

*** Can't find github.com: No answer

Authoritative answers can be found from:

github.com

origin = ns-1707.awsdns-21.co.uk

mail addr = awsdns-hostmaster.amazon.com

serial = 1

refresh = 7200

retry = 900

expire = 1209600

minimum = 86400

$ nslookup -type=mx github.com

Server: 8.8.8.8

Address: 8.8.8.8#53

Non-authoritative answer:

github.com mail exchanger = 1 aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com mail exchanger = 10 alt3.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com mail exchanger = 10 alt4.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com mail exchanger = 5 alt1.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com mail exchanger = 5 alt2.aspmx.l.google.com.

Authoritative answers can be found from:

To get all the relevant information there is also an any option

$ nslookup -type=any github.com

;; Truncated, retrying in TCP mode.

Server: 8.8.8.8

Address: 8.8.8.8#53

Non-authoritative answer:

Name: github.com

Address: 20.207.73.82

github.com nameserver = dns1.p08.nsone.net.

github.com nameserver = dns2.p08.nsone.net.

github.com nameserver = dns3.p08.nsone.net.

github.com nameserver = dns4.p08.nsone.net.

github.com nameserver = ns-1283.awsdns-32.org.

github.com nameserver = ns-1707.awsdns-21.co.uk.

github.com nameserver = ns-421.awsdns-52.com.

github.com nameserver = ns-520.awsdns-01.net.

github.com

origin = ns-1707.awsdns-21.co.uk

mail addr = awsdns-hostmaster.amazon.com

serial = 1

refresh = 7200

retry = 900

expire = 1209600

minimum = 86400

github.com mail exchanger = 1 aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com mail exchanger = 10 alt3.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com mail exchanger = 10 alt4.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com mail exchanger = 5 alt1.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com mail exchanger = 5 alt2.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com text = "MS=6BF03E6AF5CB689E315FB6199603BABF2C88D805"

github.com text = "MS=ms44452932"

github.com text = "MS=ms58704441"

github.com text = "adobe-idp-site-verification=b92c9e999aef825edc36e0a3d847d2dbad5b2fc0e05c79ddd7a16139b48ecf4b"

github.com text = "apple-domain-verification=RyQhdzTl6Z6x8ZP4"

github.com text = "atlassian-domain-verification=jjgw98AKv2aeoYFxiL/VFaoyPkn3undEssTRuMg6C/3Fp/iqhkV4HVV7WjYlVeF8"

github.com text = "docusign=087098e3-3d46-47b7-9b4e-8a23028154cd"

github.com text = "facebook-domain-verification=39xu4jzl7roi7x0n93ldkxjiaarx50"

github.com text = "google-site-verification=UTM-3akMgubp6tQtgEuAkYNYLyYAvpTnnSrDMWoDR3o"

github.com text = "krisp-domain-verification=ZlyiK7XLhnaoUQb2hpak1PLY7dFkl1WE"

github.com text = "loom-site-verification=f3787154f1154b7880e720a511ea664d"

github.com text = "stripe-verification=f88ef17321660a01bab1660454192e014defa29ba7b8de9633c69d6b4912217f"

github.com text = "v=spf1 ip4:192.30.252.0/22 include:_netblocks.google.com include:_netblocks2.google.com include:_netblocks3.google.com include:spf.protection.outlook.com include:mail.zendesk.com include:_spf.salesforce.com include:servers.mcsv.net ip4:166.78.69.169 ip4:1" "66.78.69.170 ip4:166.78.71.131 ip4:167.89.101.2 ip4:167.89.101.192/28 ip4:192.254.112.60 ip4:192.254.112.98/31 ip4:192.254.113.10 ip4:192.254.113.101 ip4:192.254.114.176 ip4:62.253.227.114 ~all"

github.com rdata_257 = 0 issue "digicert.com"

github.com rdata_257 = 0 issue "globalsign.com"

github.com rdata_257 = 0 issuewild "digicert.com"

Authoritative answers can be found from

dig Link to heading

The dig command provides more detailed information than nslookup. Here’s the description from dig’s man page:

dig (domain information groper) is a flexible tool for interrogating DNS name servers. It performs DNS lookups and displays the answers that are returned from the name server(s) that were queried. Most DNS administrators use dig to troubleshoot DNS problems because of its flexibility, ease of use and clarity of output. Other lookup tools tend to have less functionality than dig.

Let’s see an example using dig’s trace option which performs iterative queries and display the entire trace path to resolve a domain name

dig +trace github.com

; <<>> DiG 9.10.6 <<>> +trace github.com

;; global options: +cmd

. 86251 IN NS a.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS b.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS c.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS d.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS e.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS f.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS g.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS h.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS i.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS j.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS k.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS l.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN NS m.root-servers.net.

. 86251 IN RRSIG NS 8 0 518400 20230215060000 20230202050000 951 . shgCtuO0XufPswkzQkwltbwHBi4HlRtWdCGcMAS68gBzwmiEcpL2irkl ZpKY73M0vDj7Bm6Eagwp18u3FtHNDjcp2pQRXSz6dNeQAYYPsb38xrGU 3SmCSY6MYchSNX/Jc5+f49woVaErv1zhV5ZnHkjOMDY3LGjQ0V4dR2iT fk+SEydfBZDlsvkQIGv7R1Q2Gh4EtGoOu0awOKir1XD4cDHpfce6kBax OB2DQaom4J6UsHUfd+jQlQ6U/Ro7EkX9LYDHGvwq3qpTvSs0IQNg4jwu k13EtAq/F7pTecqBb/AzEbTxu3HgTUIUoWgBfQ1ICYPQAWwFzqrFvILd YXgiRQ==

;; Received 525 bytes from 8.8.8.8#53(8.8.8.8) in 20 ms

com. 172800 IN NS a.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS b.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS c.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS d.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS e.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS f.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS g.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS h.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS i.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS j.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS k.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS l.gtld-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS m.gtld-servers.net.

com. 86400 IN DS 30909 8 2 E2D3C916F6DEEAC73294E8268FB5885044A833FC5459588F4A9184CF C41A5766

com. 86400 IN RRSIG DS 8 1 86400 20230215060000 20230202050000 951 . eeX+SIe/mrEDaX+91XtQusdd0RPqPcDZubR7ChRGkR4za67c1Ax5mhpo 07KpYnmMpg4pS/mmRMLl5dbi5j9kwvkoKYw0gx8xz6Y173/qYhXm5ihf bitvV8ueuq5bbnHmAwLdf8QLj4xY92X0mbhg6UNUKCRbIQNXQsLmXqHQ ax2SPfi98Dt8/cBCnFjfk16jrekERSXJlIliampc/KljHHYMsaZBwpnh 1mxAIYwQ7xDlvPVUzQfhBTZ8VC/ZBZ4VNldCYkhn/e9eBEOReUl8Zm/G QXYhlzQ2lV44rKEwlDH9EDwbc6jV6YLqzs6MJ9ZJfmcRSzlK235X3rkl mCAQUQ==

;; Received 1170 bytes from 2001:7fd::1#53(k.root-servers.net) in 129 ms

github.com. 172800 IN NS ns-520.awsdns-01.net.

github.com. 172800 IN NS ns-421.awsdns-52.com.

github.com. 172800 IN NS ns-1707.awsdns-21.co.uk.

github.com. 172800 IN NS ns-1283.awsdns-32.org.

github.com. 172800 IN NS dns1.p08.nsone.net.

github.com. 172800 IN NS dns2.p08.nsone.net.

github.com. 172800 IN NS dns3.p08.nsone.net.

github.com. 172800 IN NS dns4.p08.nsone.net.

CK0POJMG874LJREF7EFN8430QVIT8BSM.com. 86400 IN NSEC3 1 1 0 - CK0Q2D6NI4I7EQH8NA30NS61O48UL8G5 NS SOA RRSIG DNSKEY NSEC3PARAM

CK0POJMG874LJREF7EFN8430QVIT8BSM.com. 86400 IN RRSIG NSEC3 8 2 86400 20230207052257 20230131041257 36739 com. bIC3JRS3i5tgfH6Kn2lqyHxTgaWT5HPky5puq3ue83uT+ahEG6nNnuR8 ydUphSSrvIYJBJ1ny0zEG1AG/4NLRiaULJzu4TCW7i6Nh5uD/7x+n1Jp v87utrvOtBslzssHr4rBX/tyi/k8dzDl4DwWdeaVdY4aTiP++q/ePyOI sYiaflykYTR9YJVvL4AyoXClBFGMW9MUWLv6DtMNl2w8Lg==

4KB4DFS71LEP8G8P8VT4CCUSQNL4CNCS.com. 86400 IN NSEC3 1 1 0 - 4KB4PTQQ5CTA7POCTGM7RUFC8B1RKTEU NS DS RRSIG

4KB4DFS71LEP8G8P8VT4CCUSQNL4CNCS.com. 86400 IN RRSIG NSEC3 8 2 86400 20230208055340 20230201044340 36739 com. JC1p1yrAzea9WEGnT1b3c9caxuwpz0ZXcanV+PQG8HDy98hRIG4+TNXM i0mnDjMAN61OtthOKWqbucchfRcHPHWwF/SXrtCBAlgsvp/QAHcHPInb F3MQu6rqXDkQJXkRqT6Zf3bigSzLg0E4ysPpK+vDaDZYOHrrB7u59HVb pKskzTowIKt+eTnvF4dDo3FPTvwfy4i0AN102b8OgirCaQ==

;; Received 827 bytes from 192.33.14.30#53(b.gtld-servers.net) in 41 ms

github.com. 60 IN A 20.207.73.82

;; Received 55 bytes from 198.51.45.8#53(dns2.p08.nsone.net) in 44 ms

The above output shows DNS lookup information for github.com domain. The output shows A record, SOA Record, DNSEC, root servers used for lookup, and other relevant information associated with this domain.

Conclusion Link to heading

The Domain Name System (DNS) is a crucial component of the internet, acting as a translator between human-readable domain names and machine-readable IP addresses. Throughout this article, we’ve explored:

- The basic function of DNS and its importance in internet communication

- The step-by-step process of DNS resolution

- Key DNS record types such as A, AAAA, CNAME, and PTR

- The roles of different types of nameservers

- Security enhancements like DNSSEC and NSEC

- Troubleshooting tools including nslookup and dig

Understanding DNS is essential for anyone working with web technologies. By grasping these concepts and utilizing the tools discussed, you’ll be better equipped to navigate, manage, and troubleshoot internet-based systems and services.